A Russian Connection

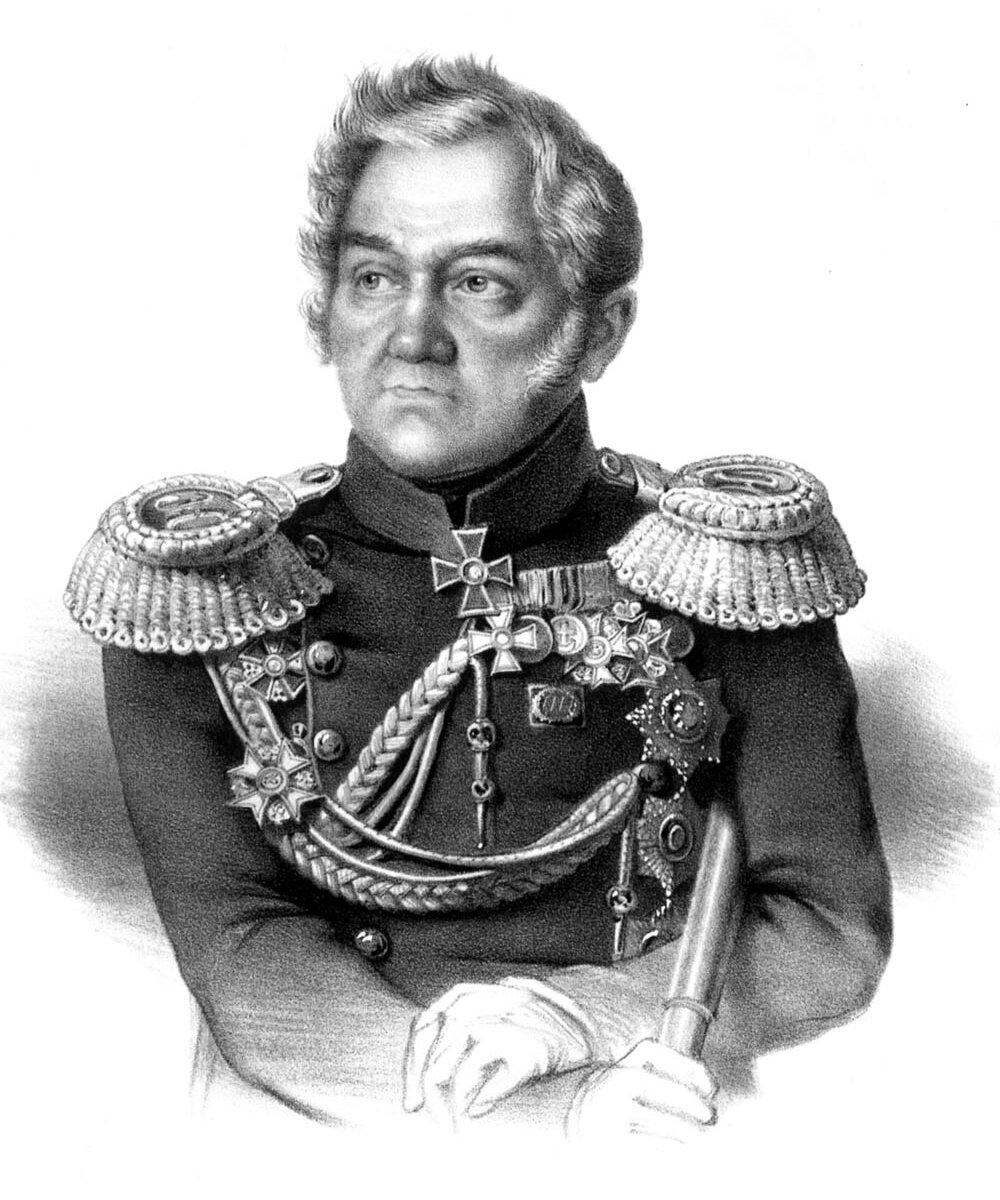

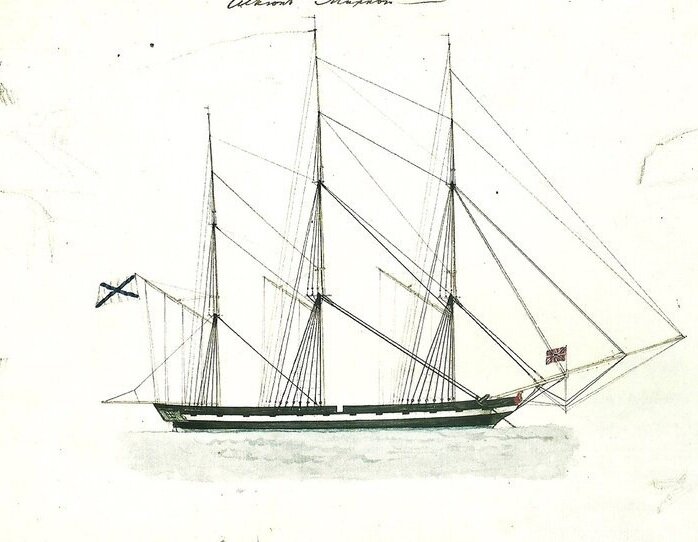

In 1820 the Kurahaupō iwi of Te Tauihu o Te Waka a Māui (Top of the South Island) were visited by the Russians in a two-ship expedition led by Fabian Gottlieb Benjamin von Bellingshausen (pictured on the left) on board the Vostok and Mikhail Lazarev (pictured on the right) on board the Mirny.

The Kurahaupō iwi occupying those lands were, Ngāti Kuia, Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō and Rangitāne o Wairau. These same people encountered Cook and his men fifty years earlier.

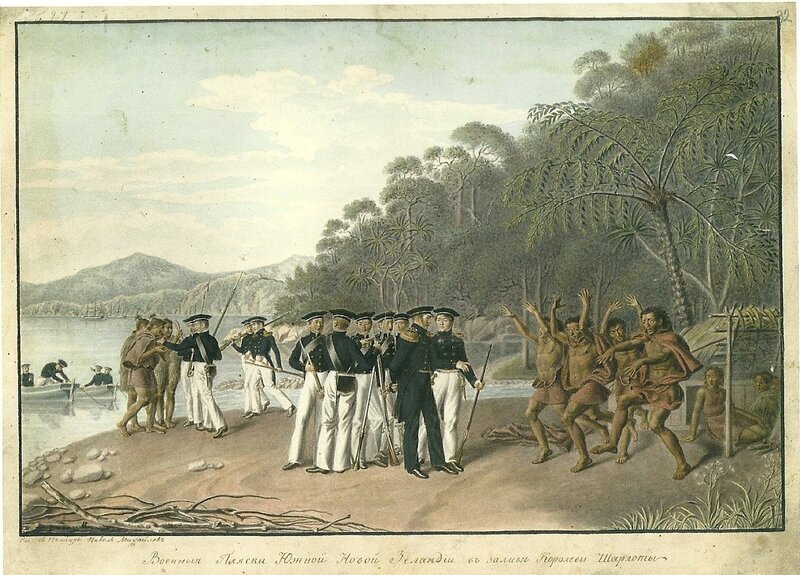

haka being performed to welcome visitors to Queen Charlotte Sound on 30 May 1820. From the album of Pavel Mikhailov's. Public Domain.

The Russians had recently circumnavigated Antarctica and had started making their way to the warmer climates of the Pacific. During their voyage north, they struck bad weather off the coast of New Zealand, and rough Tasman seas forced the expedition to seek shelter in Tōtaranui (Queen Charlotte Sound). Bellingshausen, who was familiar with Cook’s charts and journals, knew of a place where they could shelter from the prevailing winds of the Cook Strait and the Tasman Sea.

Once anchored off Meretoto (Ships Cove) in Tōtaranui, the Russians were greeted by two waka, one of which was manned by an older male – most likely a rangatira (chief). This rangatira was invited to come aboard the Vostok, where he was greeted by Bellinghausen.

As mentioned, Bellingshausen had copies of Cook’s charts and journals, including a list of Māori words he had recorded. Using those words, Bellingshausen was able to communicate his need for food, such as ika (fish).

A sketch of Sloop Mirny, captained by Mikhail Lazarev. from the album of Pavel Mikhailov (1820). Public Domain

Once trust had been established between Māori and the Russians, trading started between the two cultures.

Unlike other foreign visitors, the Russians had no plans of claiming lands or bringing harm to the indigenous peoples. Their purpose was scientific, with only good intentions to trade and collect taonga (treasures) from different cultures.

Before leaving Russia, Bellingshausen and Mikhail had stocked their ships full of non-essential cargo, such as knives, nails, mirrors and much more. These were used for trading with the indigenous peoples as they travelled around the Pacific and other countries collecting taonga.

During their visit to Meretoto, the Russians collected an impressive array of taonga Māori, from finely woven kākahu (cloaks), elegantly carved wakahuia (treasure boxes), and weapons of all types. An entry in Bellingshausen’s journal talks of a young tāne (man) who did not want to trade his pounamu whao (greenstone chisel), which he wore around his neck with the Russian traders. Eventually, this tāne noticed a single piece of paper, which intrigued him so much, he traded his taonga for the paper.

Also present on this expedition was artist Pavel N. Mikhaylov who sketched the encounters between the two cultures. In his sketches, Mikhaylov managed to capture styles and designs unique to Te Tauihu, such as tā moko (traditional tattooing patterns), hairstyles, traditional clothing and how they were worn, carving styles and layout of kāinga (village).

The taonga collected by Bellingshausen and his crew returned to Russia. They were distributed between the Kunstkamera Museum in St Petersburg and the Kazan Federal University.

Panorama of Kazan State University Where some of Bellingshausen’s collected taonga are held. Image Created By Bushy moustache at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0,

Although these taonga now reside on the other side of the world, they are safe, and more importantly, they still exist physically. These taonga give insight into what life would have been like 200 years ago, connecting the past to the present. The taonga represents much more than just beautiful objects – they act as a resource for cultural revitalisation.

Despite what other stories tell, the taonga collected in 1820 still have a living whakapapa (heritage), and a connection to their living descendants: Ngāti Kuia, Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō and Rangitāne o Wairau.

Article written by our Kaitiaki Taonga Māori, Hamuera Robb (Ngāti Kuia, Ngāti Apa ki te Rā Tō, Rangitāne o Wairau, Ngāti Koata, Ngāti Toa and Ngāi Tahu)